Gotchas with SQLite in Production

SQLite has been getting much attention lately as a good database for production web applications. It’s especially popular with those who strive to keep their web application stack as simple as possible (See DHH’s Twitter posts).

While SQLite can be the perfect choice for many web applications, a few gotchas might ruin your day. Knowing what these gotchas are will help you decide whether or not SQLite is a good fit for your use case.

Database size

Before diving into the gotchas, I want to dispel the myth that “SQLite is only appropriate for small datasets.” The theoretical limit for a SQLite database is 281 terabytes, so most applications will never come close. You can read more about this and other limits in the SQLite documentation.

The point is that as your database grows, you’ll run into the same type of issues that you would with Postgres or MySQL. You can usually solve these issues by creating the correct indexes or optimizing your queries.

However, there are some gotchas specific to SQLite not related to database size. Let’s take a look at them.

1. Gotcha: Configuration

Out of the box, SQLite is not configured for multi-threaded access. You have to make sure to configure it properly. In most cases, this is as simple as running the following PRAGMAs:

PRAGMA foreign_keys = ON;

PRAGMA journal_mode=WAL;

PRAGMA synchronous=NORMAL; -- this might roll back a committed transaction following a power loss or system crash, use with caution

PRAGMA mmap_size = 134217728;

PRAGMA journal_size_limit = 27103364;

PRAGMA cache_size=2000;

In Rails, this is done by default. In Django, you currently have to do some of these PRAGMA’s manually (see my blog post about it), but this might change in the future.

2. Gotcha: No connections over the network

One of SQLite’s main strengths is its single-file design, which frees you from configuring ports, setting up users and passwords, and configuring connection pools. However, this drawback makes it much more challenging to connect to the database from another machine.

Typically, there are two reasons for a web application to run on multiple machines:

- Horizontal scaling

- High availability

These days, you can vertically scale a single machine to 192 vCPUs and 768 GiB memory, making it possible to avoid horizontal scaling altogether. Unless, of course, you need to run specific workloads on specialized hardware (e.g., GPUs) and then store the results in your primary database.

Suppose your whole application is going to run on a single machine. In that case, you will have problems assuring high availability when applying OS updates and doing maintenance. You can still achieve three nines, which should be enough for most web apps, but for anything more than that, you will need to make sure your application runs on more machines, which makes SQLite a lot less appealing.

In practice, the most annoying thing about this is that you can’t easily connect to your production database with a GUI tool from your dev machine. Most clients like DataGrip don’t support connecting to SQLite via SSH.

There are also reimplementations of SQLite that try to remove the single machine limitation: libSQL, rqlite, and others. However, these projects quickly become more complex than Postgres or MySQL, so use them cautiously.

3. Gotcha: Network and ephemeral file systems

A possible solution for the previous gotcha would be to put the SQLite database on a network file system and have it synced to multiple machines. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work because network file systems usually don’t have the required lock-level guarantees, which means you can end up with a corrupt database. A solution for this is LiteFS, a file system developed for precisely this purpose. It is still limited and only creates read replicas, so it is up to you to route writes to the primary machine.

Ephemeral file systems are usually used by PaaS companies that host your application inside containers like Heroku dynos. While you can technically run your SQLite database from an ephemeral file system, all changes will be lost when the container is redeployed or restarted.

Fly.io is the PaaS to consider if you want to use SQLite. It allows you to attach a proper file system to your containers. Fly invested engineering resources in developing the previously mentioned LiteFS.

4. Gotcha: Concurrency

Even with the WAL mode enabled, SQLite still limits writing to only one thread at a time. The write is per database, so writing to one table blocks writing to all other tables. This is a significant limitation, especially compared to MySQL and Postgres, which have per-table or even per-row locks.

This isn’t a deal breaker in practice since you can usually keep write queries short and fast. Your application can still have A LOT of throughput - especially since fast SSDs are cheap these days. Not many applications require more than 2000 writes per second, which I got with Django + SQLite on a 20 euro Hetzner instance, and the bottleneck was Django.

Suppose your use case requires continuous heavy writes into multiple tables in parallel. To make this faster with SQLite, you can split your tables across multiple databases. This way, each database can write to its set of tables in parallel. Before going down this road, consider using MySQL or Postgres instead, as they might make your application code simpler.

If you have continuous writes, you might also encounter a WAL issue where the checkpoint doesn’t flush the .wal file data in the main database file. This can make your .wal file grow very large. The solution is WAL2 mode. However, it’s still experimental, and you’ll have to compile your version of SQLite to enable it.

5. Gotcha: Transactions

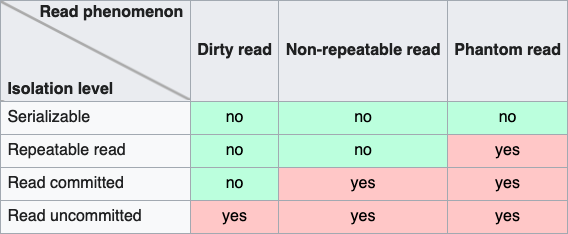

Transactions in SQLite are serializable, but for web applications, read committed is usually good enough and the default for many frameworks (Django included). You can choose your transaction isolation level in PostgreSQL and MySQL but are stuck with serializable in SQLite.

SQLite implements serializable transactions by using read or read-write locks. With WAL mode, you can have multiple read transactions but only one read-write transaction at a time. Read transactions can run concurrently even when a read-write lock is in place. This means that as long as you are only reading inside a transaction, you won’t have problems with high concurrency, but you’ll run into throughput issues when you have multiple write transactions. There is a BEGIN CONCURRENT mode in development that should improve this, but it’s only available as an experimental branch. The only way to improve throughput problems with write transactions is to ensure your write transactions are as short as possible.

DHH himself mentioned this issue in an interview and had to optimize the transaction code in Rails to improve throughput. While transactions should be as short as possible in any application, this is even more critical in SQLite, so keep it in mind.

When working with transactions in a web application context, you should only start a transaction when you need to write something. This will simulate the read committed behavior that web frameworks default to. When you start a write transaction, always use BEGIN IMMEDIATE instead of a regular BEGIN. This is because a read transaction cannot be upgraded to a write transaction, so you’ll see database is locked errors not retrying until the BUSY_TIMEOUT runs out. I’ve written a separate blog on Database is Locked errors, where I cover this in more detail.

6. Gotcha: Backups

You might be tempted to copy/paste the SQLite file to create a backup, but this is a bad idea as it can corrupt the backup file. Instead, you should always use the VACUUM INTO command to create a full backup.

For online backups, you must use a third-party tool like LiteStream to copy changes to an S3 bucket every few seconds. libSQL also provides great backup options, including S3.

If you need higher durability guarantees, there are projects that implement raft-based consensus in SQLite (rqlite, dqlite). Postgres and MySQL provide more replication options like synchronous replication, so achieving these guarantees is more straightforward than in SQLite.

7. Gotcha: Migrations

SQLite has limited support for the ALTER TABLE statement, which relational schema migration tools rely upon. Only adding and dropping columns and renaming tables are supported. This can make your database migrations more complicated. See the Alembic guide on SQLite to see some of the challenges.

Simon Willison’s sqlite-utils include a solution for this problem. Read more about it in the transforming a table section in the docs.

Conclusion

The main benefit that you are getting with SQLite is lower operational complexity. If you want to get your application running on a single machine and forget about it there is no better choice.

Psst: I have also talked about my experience of using SQLite at DjangoCon Europe 2024 here’s the 🎥 video. As soon as you need multiple machines, have a write-heavy workload, or long-running transactions, SQLite becomes less appealing, and you are better off using a more traditional database like MySQL or Postgres. However, most web applications can run on a single machine, have read-heavy workloads, and can avoid long running transactions. For these, SQlite can be the perfect choice!